Concurrency:

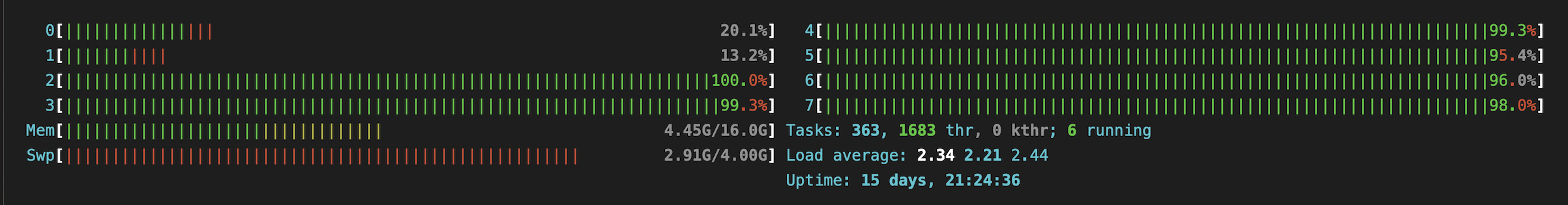

Imagine you have several tasks or threads labeled T1, T2, and T3, and they’re all being processed by a single-core processor. Concurrency occurs when these threads are in different execution stages simultaneously but not advancing together.

Picture this on a single-core processor: threads T1, T2, and T3 are switched in and out swiftly by the operating system. This switching is so fast it seems as though the system is doing many things at once. But in reality, each task takes its turn on the processor, one after the other. For example, at a certain point—let’s call it p4—T1 might be halfway done, T2 only a quarter done, and T3 hasn’t started at all. Although they appear to be running together, in reality, they’re each taking turns to execute their code sequences.

Parallelism:

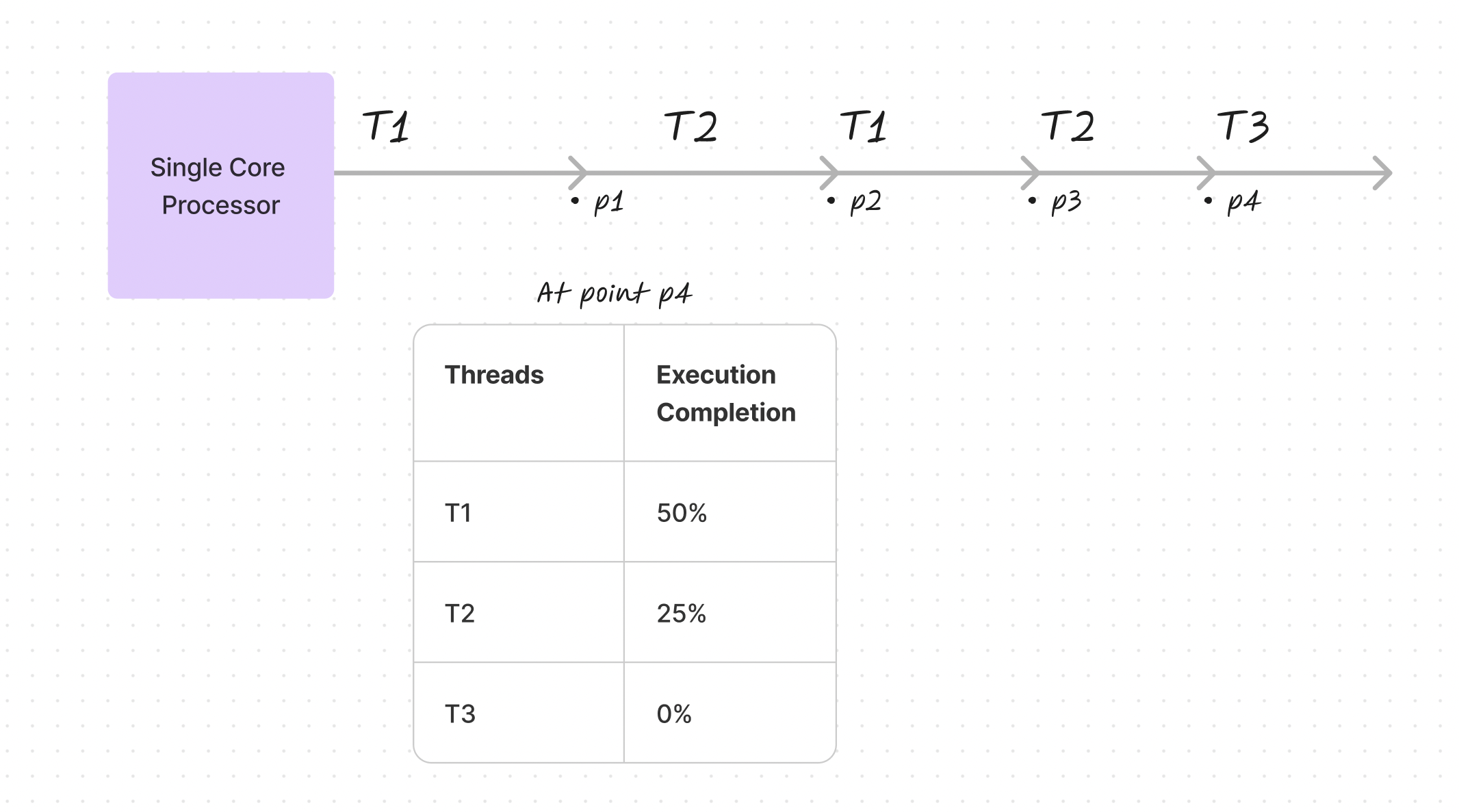

Parallelism comes into play when you have more than one processor, allowing multiple threads to truly execute simultaneously. This means progress is made on several threads at the same time.

In the above diagram, it’s clear that with more than one processor—Core 1 and Core 2—different tasks (T1, T2, T3, T5) can be executed concurrently without waiting for each other. At points like p1, p2, and p3, different tasks have genuinely advanced simultaneously, representing real parallel execution.

Context Switching:

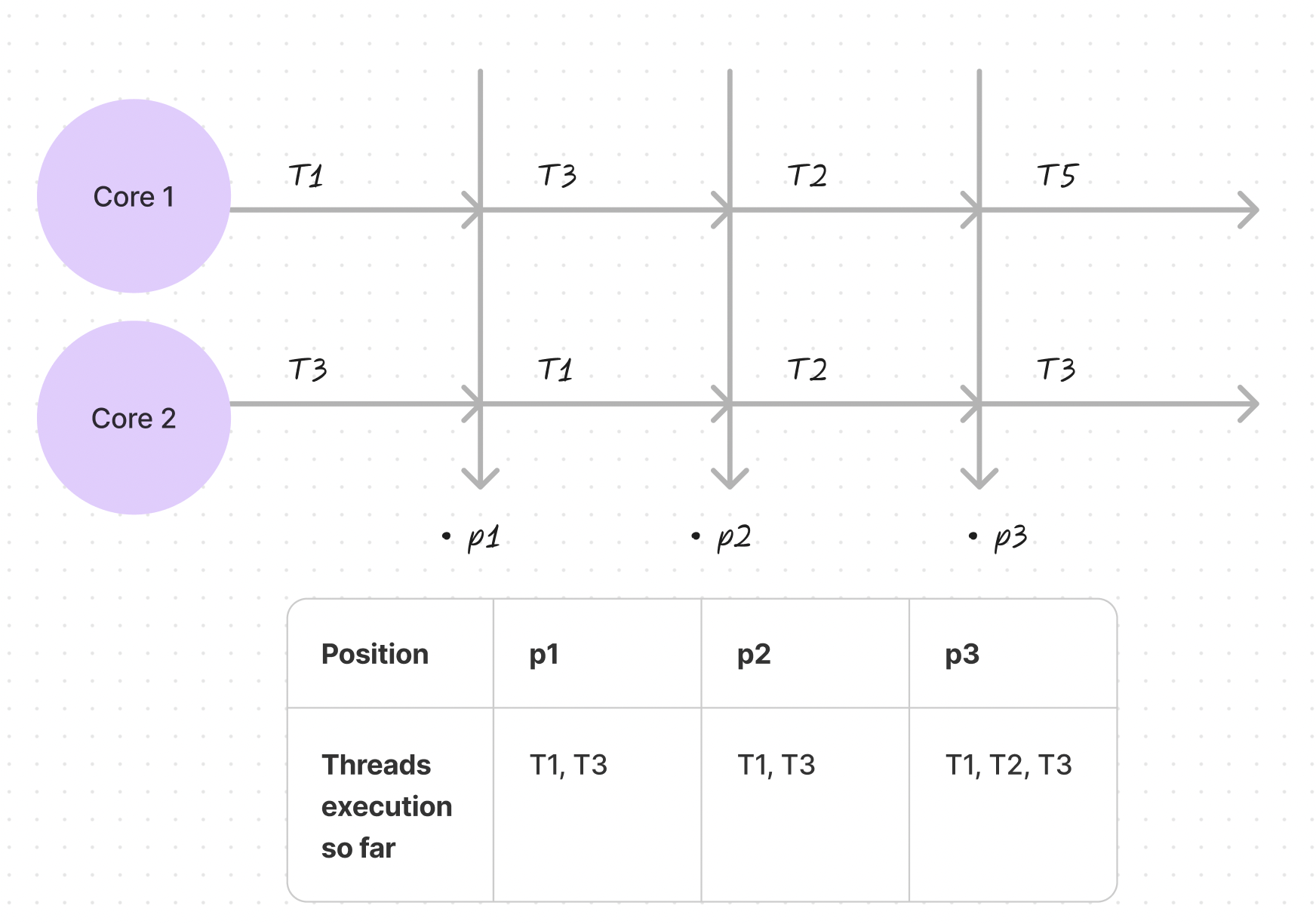

It’s not always beneficial for a system to switch between tasks too frequently. This concept is easier to grasp with the following illustration:

In this scenario, we observe that excessive switching can delay task completion. For instance, in version 2, where T1 is fully executed before moving on to T2, tasks are completed more swiftly compared to version 1, which switches contexts frequently. Such switching uses up considerable CPU time and cycles to remember and restore the last known state of a task. Context switching refers to the time consumed to preserve a process’s state in memory and to retrieve it later for continued execution.

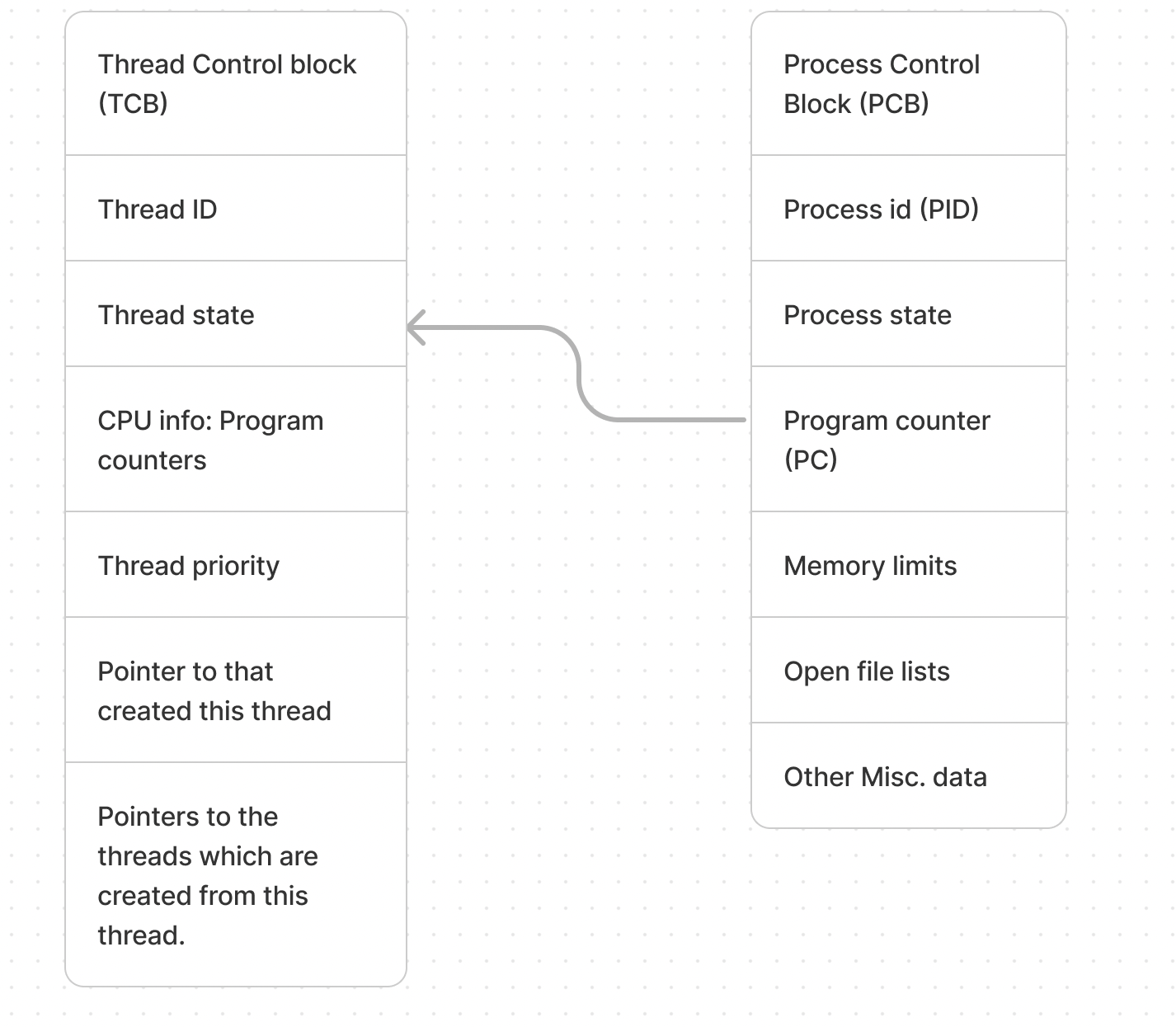

Process Control Block and Thread Control Block:

The system keeps track of the process state in memory with a data structure known as the Process Control Block (PCB). The PCB includes important information about the process such as its unique identifier (PID), its current state, and the program counter that indicates where to resume execution. This data is crucial for the operating system to manage context switching efficiently, allowing it to pause a process, save its state, and later resume it from the same point.

Since each process may have multiple threads, there’s a separate structure to manage this information, called the Thread Control Block (TCB). The TCB holds details about individual threads within a process, including each thread’s ID, state, CPU registers, priority, and references to any threads it creates or that were created by it. Together, PCB and TCB provide the operating system with the information needed to manage multiple processes and threads, ensuring each thread can be tracked and managed independently.

Writing code that leverages a CPU’s multicore capabilities is advantageous. For example, consider Google Docs, which simultaneously performs multiple tasks like grammar checking, offering suggestions, and autosaving documents, all thanks to parallel processing. Here’s a simple illustration of how to use threads for true parallelism in Java: Firstly, create a class that implements the Runnable interface:

public class HelloWorld implements Runnable{

@Override

public void run() {

System.out.println("Hello World 1 - " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

System.out.println("Hello World 2 - " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

}

}

Next, define the main class that will create and start the threads:

public class ThreadsExample {

public static void main(String[] args){

for(int i = 0; i< 10; i++){

// 1. Create a object of class for which you want to run it on threads

HelloWorld helloworld = new HelloWorld();

// 2. Next pass the object to the Thread class

Thread thread = new Thread(helloworld);

System.out.println("-------------------------");

System.out.println("1 - " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

System.out.println("2 - " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

thread.start();

System.out.println("3 - " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

System.out.println("4 - " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

System.out.println("------------------------\n");

}

}

}

Output :

-------------------------

1 - main

2 - main

3 - main

Hello World 1 - Thread-0

4 - main

------------------------

Hello World 2 - Thread-0

-------------------------

1 - main

2 - main

3 - main

4 - main

------------------------

Hello World 1 - Thread-1

Hello World 2 - Thread-1

-------------------------

.

.

.

.

.

When running the ThreadsExample program in Java, the output illustrates parallelism in action. The main thread prints lines “1 - main” through “4 - main,” while new threads execute the “Hello World” statements. The interleaved output indicates that the “Hello World” statements are not necessarily printed between “1 - main” and “4 - main” consistently. Instead, they occur at various points during the main thread’s execution, showcasing that the newly created threads are operating concurrently. For instance, after “3 - main” is printed, “Hello World 1 - Thread-0” is executed, followed by “4 - main.” This indicates that Thread-0 is running in parallel with the main thread. In some cases, both “Hello World 1” and “Hello World 2” from the same thread are executed back-to-back, while in others, they’re separated by the main thread’s output. Such a pattern of execution exemplifies parallelism; different threads are running simultaneously, utilizing the CPU’s multicore capabilities. This means the CPU is processing multiple threads at the same time, rather than sequentially, allowing tasks to be completed faster and more efficiently.

What are Threads in Ruby

In Ruby, a thread is like a separate task that can run at the same time as other tasks in your program. Imagine you’re in a kitchen cooking dinner, and you’ve got several pots on the stove — each pot could be thought of as a thread. Ruby lets you manage these pots so you can get several things done at once, like boiling pasta while simmering sauce.

But there’s a catch. In Ruby’s main version (MRI), it’s as if you can only turn up the heat on one pot at a time. That’s because of something called the Global Interpreter Lock, or GIL for short. It’s a rule that says only one bit of the program can use the central part of Ruby at once. So even if you’ve got several pots, or threads, they have to take turns.

On the other hand, Java is like having several stoves with their own burners; each pot can be heated at the same time. This is because Java can actually do many things at once, for real, which is known as true parallel execution. Java’s threads are more independent and can work simultaneously, letting your program do multiple tasks at the same time more efficiently.

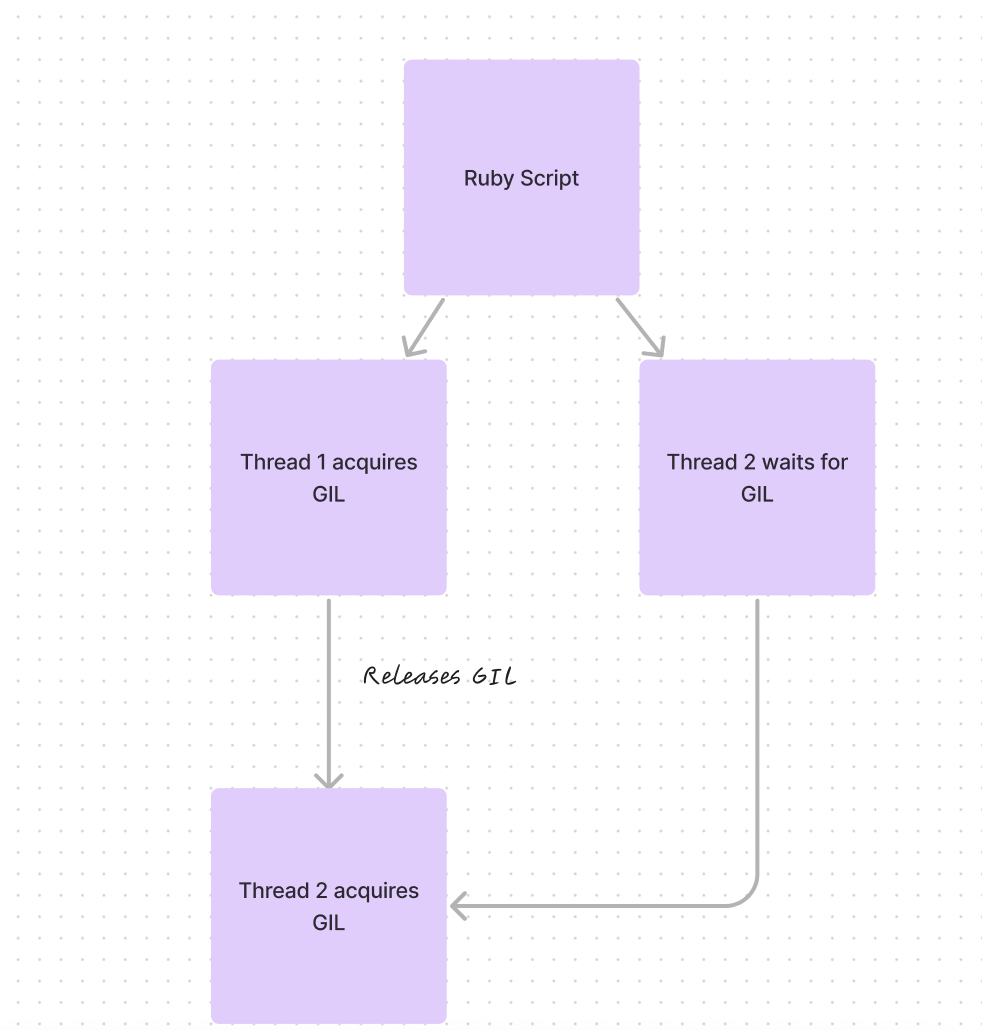

Understanding the GIL (Global Interpreter Lock) in Ruby

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), also known as the Global VM Lock (GVL) in the context of Ruby, is a mechanism used in computer languages that have a garbage-collected heap of memory accessible from multiple threads. The main reason for the GIL’s existence in Ruby (specifically the default Ruby interpreter, MRI) is to simplify the C extension API and to make internal data structures easier to manage by making the Ruby interpreter thread-safe. Essentially, it ensures that only one thread can execute Ruby code at a time, even if multiple threads are available.

Think of the GIL in Ruby like traffic control in a busy city. It’s like having a single lane where only one car can pass at a time. This keeps traffic orderly and prevents accidents in places where the road might not be wide enough for two cars to pass side by side. In Ruby, the GIL prevents different parts of your program, or “threads,” from getting into each other’s way when they want to work at the same time.

Why Can’t We Ignore the GIL?

Ignoring the GIL in MRI Ruby is not possible without modifying the interpreter itself because it is deeply integrated into its architecture. The GIL prevents race conditions and ensures thread safety by avoiding the scenario where multiple threads modify the same memory area concurrently. Without the GIL, MRI’s internal data structures could become corrupted, leading to unpredictable behavior.

Using JRuby to Bypass the GIL

JRuby, an implementation of Ruby on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), does not have a GIL. It allows Ruby code to execute concurrently on multiple JVM threads, leveraging the JVM’s native thread support and advanced garbage collection. This makes JRuby a good choice for running concurrent Ruby applications that can take full advantage of multi-core processors.

Using Processes for Parallelism in Ruby

Achieving true parallelism in Ruby can be done using processes instead of threads. This is because, while threads are subject to the limitations of the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in the standard Ruby interpreter (MRI), processes run independently of each other, each with its own GIL and memory space.

Ruby’s Process module allows us to create new processes to achieve parallel computing. Let’s explore how to calculate prime numbers in a range using multiple processes.

First, we’ll look at a single-process approach:

range = 1..10_000_000

start_range = 1

end_range = 10_000_000

Using benchmarking, we measure how long it takes to calculate prime numbers in the range with a single process:

require 'prime'

Benchmark.bm do |x|

x.report("Sequential Prime Caluluation:") do

primes = Prime.each(end_range).select { |p| p >= start_range }

primes

end

end

user system total real

Sequential Prime Caluluation: 8.762962 0.153832 8.916794 ( 8.949819)

Sequential Prime Caluluation: 8.715786 0.144746 8.860532 ( 8.863357)

Sequential Prime Caluluation: 8.743539 0.149986 8.893525 ( 8.900347)

The average time for three runs was approximately 8.74 seconds.

Next, let’s test the multi-process implementation:

Benchmark.bm do |x|

x.report("Parallel Prime Calculation:") do

num_processes.times.map do |i|

start_range = range.first + i * slice_size

end_range = start_range + slice_size - 1

end_range = range.last if i == num_processes - 1

Process.fork do

# Each process will handle a subset of the range

primes = Prime.each(end_range).select { |p| p >= start_range }

# If needed, do something with the primes here

end

end

Process.waitall

end

end

user system total real

Parallel Prime Calculation: 0.000360 0.003311 43.477802 ( 9.868197)

Parallel Prime Calculation: 0.000439 0.004470 44.046979 ( 10.051793)

Parallel Prime Calculation: 0.000336 0.002862 44.076157 ( 10.134230)

The average time for this multi-process approach is 0.00037 secs

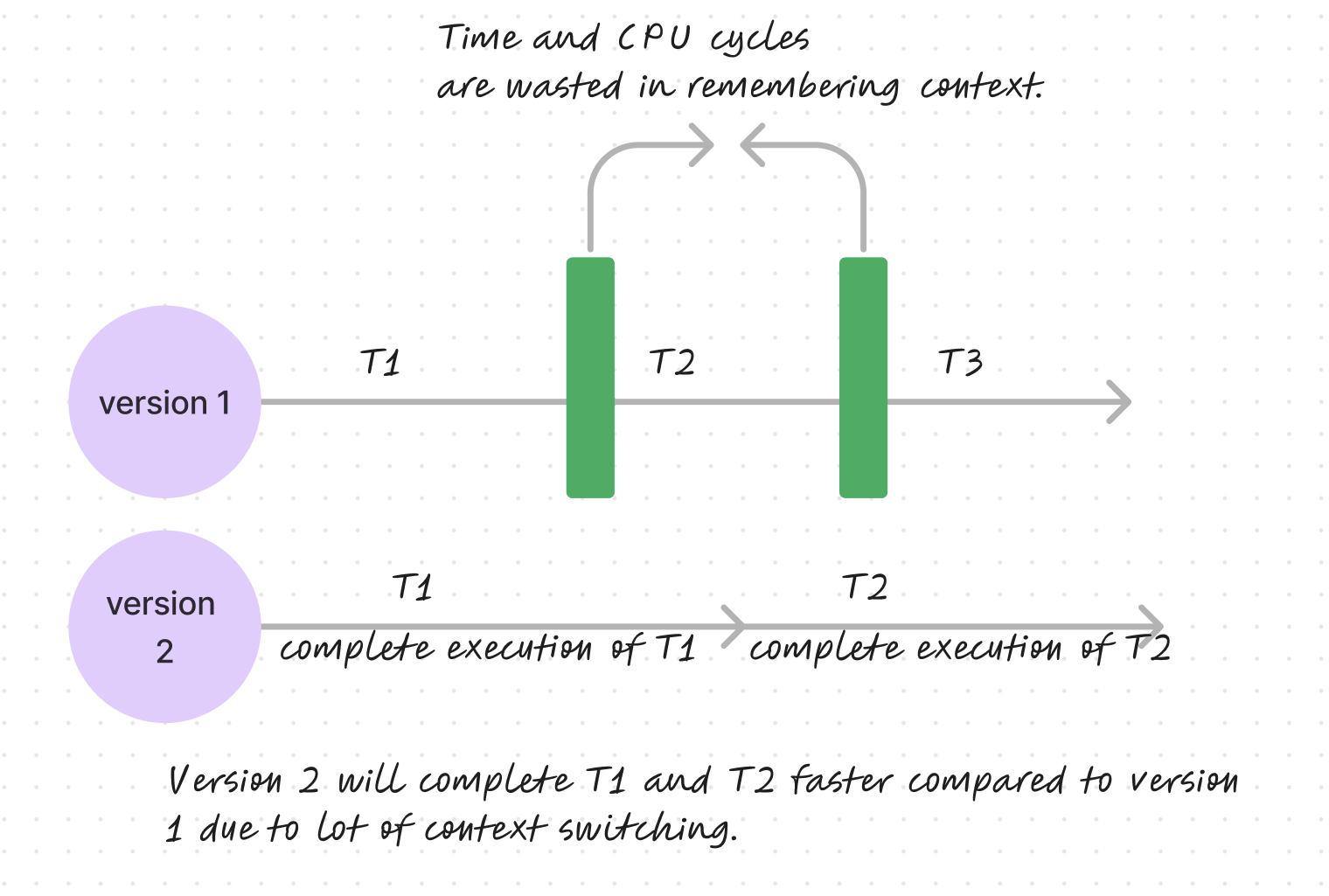

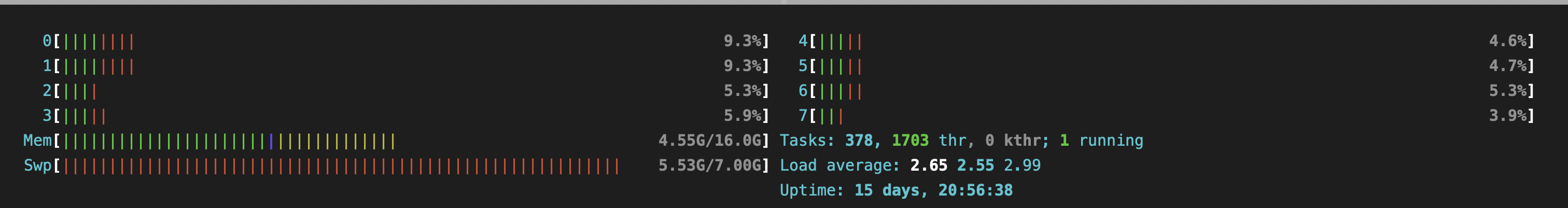

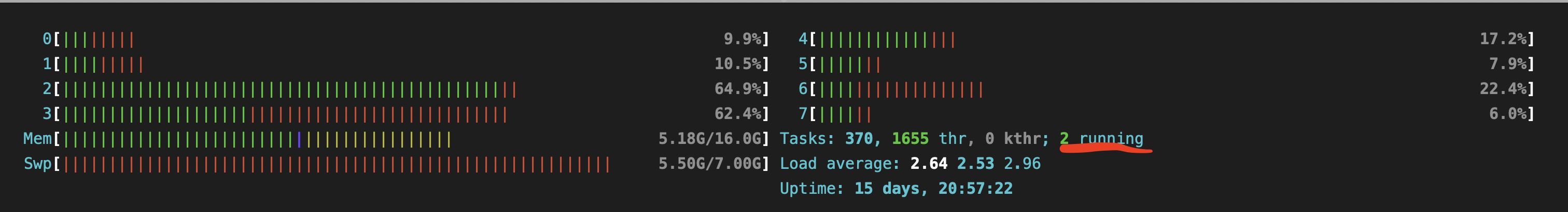

Let’s confirm the CPU utilization using htop:

Idle:

Single process implementation:

Single process implementation:

Multiple process implementation:

Multiple process implementation:

Is the Process Module a Perfect Solution?

Using multiple processes may seem like a silver bullet. However, when it comes to Ruby, creating child processes to improve performance comes with its own set of challenges and questions that developers must consider:

- Will multiple processes actually solve our problems?

- When should we choose a multi-process architecture?

- How many processes can we run simultaneously without affecting system performance?

- Do we need a mechanism to limit the number of processes?

- How can an excessive number of processes impact the system?

- Can we control the number of child processes effectively?

- What happens to child processes if the parent process terminates unexpectedly?

- When is it beneficial to use a multi-process approach?

- Creating a multi-process application can be more complex than creating a multi-threaded one.

It’s generally suitable when we have a manageable number of processes, the processes have lengthy execution times (as creating a process can be resource-intensive), we’re using a multi-core processor, and we don’t need to share data between processes—or know how to do it safely. Additionally, it’s practical when we don’t need to return data from the processes, which can be tricky. Ideally, each process operates independently, with the parent process overseeing them.